There’s often a reason why it’s hard to find examples of narrow vein models shown next to their surface analogues, whether mapped or photographed from excavations.

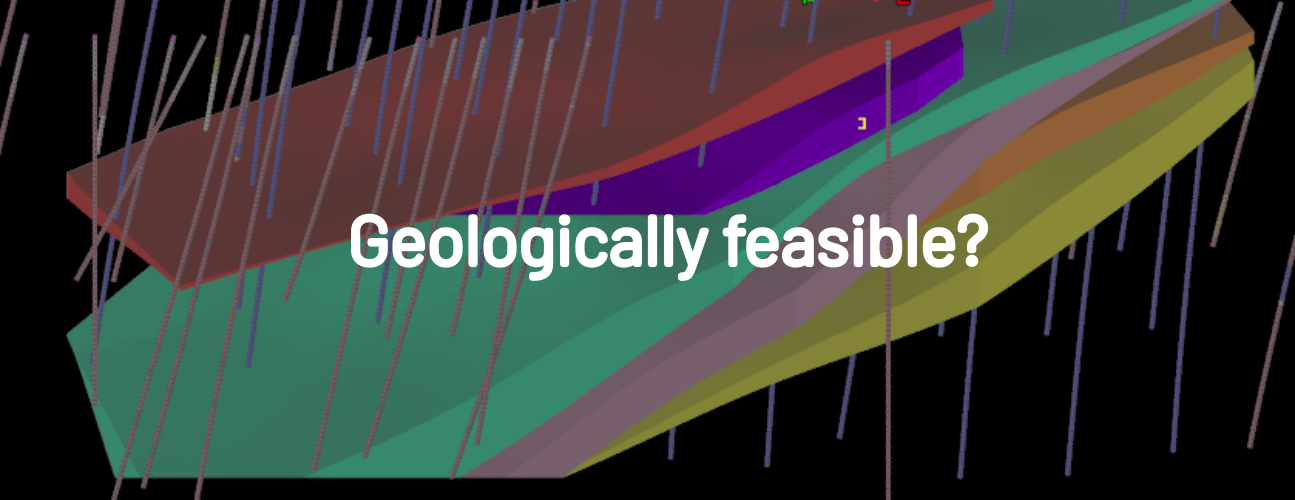

To shed light on this, here are five quick points to keep in mind when considering the geological validity of narrow vein models. These represent my own thoughts and opinions based on my own experiences; aiming to spark some critical thinking around current modelling practices:

- Sample intervals may lack the resolution needed to capture the complexities of structures hosting mineralization, especially when inadequate logging methods are employed to depict these structures initially.

- Variations in apparent vein thickness can stem from factors such as unidentified features like vein intersections, splitting, and changes in orientation, with occasional consideration for fault repeats.

- Changes in perceived orientations of singular veins often involve multiple veins from the same or similar sets instead, each with slight variations in orientation, and occasionally influenced by faulting.

- Uniform trends are frequently applied to model all structures within domains, and where these use the geochemistry for the anisotropy, just a reminder here that this has no direct link to the real structures.

- The persistence of resulting ‘veins’ defined by the modelling sometimes has no connection to observable size distributions for host veins. Some even assume full continuity by default without supporting field evidence.

Understanding there are obvious practical limitations in sampling and applying minimum mining dimensions, it’s still important to be aware of the real picture.

While some of the traditional methods used to model complex vein systems might in some way reflect potential mining approaches, making this assumption as geologists can lead to missed opportunities downstream. Why not just strive to convey our best interpretation of the real picture instead?

Issues around mining dimensions, methods, processing, and equipment selection are amplified further with the dilution introduced with block model resolution. For these reasons, its essential for geologists to have a sound understanding of the model limitations, and to play an integral role in the handover of this key information to engineers.

Want to know how to avoid these common pitfalls in the first place? In some cases, this may require a whole new approach, prioritizing as much of what we can tell around controlling structures, above spatial grade distributions which derive from these. More on this to come…